Common-pool resource

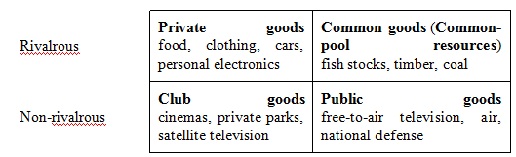

In economics, a common-pool resources (CPR), also called a common property resource, is a type of good consisting of a natural or human-made resource system (e.g. an irrigation system or fishing grounds), whose size or characteristics makes it costly, but not impossible, to exclude potential beneficiaries from obtaining benefits from its use. Unlike pure public goods, common pool resources face problems of congestion or overuse, because they are subtractable. A common-pool resource typically consists of a core resource (e.g. water or fish), which defines the stock variable, while providing a limited quantity of extractable fringe units, which defines the flow variable. While the core resource is to be protected or nurtured in order to allow for its continuous exploitation, the fringe units can be harvested or consumed.

A common property regime is a particular social arrangement regulating the preservation, maintenance, and consumption of a common-pool resource. The use of the term "common property resource" to designate a type of good has been criticized, because common-pool resources are not necessarily governed by common property regimes. Examples of common-pool resources include irrigation systems, fishing grounds, pastures, forests, water or the atmosphere. A pasture, for instance, allows for a certain amount of grazing to occur each year without the core resource being harmed. In the case of excessive grazing, however, the pasture may become more prone to erosion and eventually yield less benefit to its users. Because their core resources are vulnerable, common-pool resources are generally subject to the problems of congestion, overuse, pollution, and potential destruction unless harvesting or use limits are devised and enforced.

The use of many common-pool resources, if managed carefully, can be extended because the resource system forms a positive feedback loop, where the stock variable continually regenerates the fringe variable as long as the stock variable is not compromised, providing an optimum amount of consumption. However, consumption exceeding the fringe value reduces the stock variable, which in turn decreases the flow variable. If the stock variable is allowed to regenerate then the fringe and flow variables may also recover to initial levels, but in many cases the loss is irreparable.

Common-pool resources may be owned by national, regional or local governments as public goods, by communal groups as common property resources, or by private individuals or corporations as private goods. When they are owned by no one, they are used as open access resources. Having observed a number of common pool resources throughout the world, Elinor Ostrom noticed that a number of them are governed by common property regimes — arrangements different from private property or state administration — based onself-management by a local community. Her observations contradict claims that common-pool resources should be privatized or else face destruction in the long run due to collective action problems leading to the overuse of the core resource (see Tragedy of the commons)

Excludable Non-excludable

Common property regime

Common property regimes arise when appropriators acting independently threaten the total net benefit from common-pool resource. So in order to maintain the resource system, these regimes coordinate their strategies to keep the resource as a common property, instead of dividing it up into bits of private property. Common property regimes typically protect the core resource and allocate the fringe through complex community norms of consensus decision-making. Common resource management has to face the difficult task of devising rules that limit the amount, timing, and technology used to withdraw various resource units from the resource system. Setting the limits too high would lead to overuse and eventually to the destruction of the core resource, while setting the limits too low would unnecessarily reduce the benefits obtained by the users.

In common property regimes, access to the resource is not free, and common-pool resources are not public goods. While there is relatively free but monitored access to the resource system for community members, there are mechanisms in place which allow the community to exclude outsiders from using its resource. Thus, in a common property regime, a common-pool resource appears as a private good to an outsider and as a common good to an insider of the community. The resource units withdrawn from the system are typically owned individually by the appropriators. A common property good is rivaled in consumption.

Analysing the design of long-enduring CPR institutions, Elinor Ostrom identified eight design principles which are prerequisites for a stable CPR arrangement:

1. Clearly defined boundaries

2. Congruence between appropriation and provision rules and local conditions

3. Collective-choice arrangements allowing for the participation of most of the appropriators in the decision making process

4. Effective monitoring by monitors who are part of or accountable to the appropriators

5. Graduated sanctions for appropriators who do not respect community rules

6. Conflict-resolution mechanisms which are cheap and easy of access

7. Minimal recognition of rights to organize (e.g., by the government)

8. In case of larger CPRs: Organisation in the form of multiple layers of nested enterprises, with small, local CPRs at their bases.

Common property regimes typically function at a local level to prevent the overexploitation of a resource system from which fringe units can be extracted. There are no examples of common property regimes which solve problems of overuse on a regional scale, such as air pollution. In some cases, government regulations combined with tradable environmental allowances (TEAs) are used successfully to prevent excessive pollution, whereas in other cases — especially in the absence of a unique government being able to set limits and monitor economic activities — excessive use or pollution continue.

Adaptive governance

The management of common-pool resources is highly dependent upon the type of resource involved. An effective strategy at one location, or of one particular resource, may not be necessarily appropriate for another. In The Challenge of Common-Pool Resources, Ostrom makes the case for adaptive governance as a method for the management of common-pool resources. Adaptive governance is suited to dealing with problems that are complex, uncertain and fragmented, as is the management of common-pool resources. Ostrom outlines five basic requirements for achieving adaptive governance. These include:

• Achieving accurate and relevant information, by focusing on the creation and use of timely scientific knowledge on the part of both the managers and the users of the resource

• Dealing with conflict, acknowledging the fact that conflicts will occur, and having systems in place to discover and resolve them as quickly as possible

• Enhancing rule compliance, through creating responsibility for the users of a resource to monitor usage

• Providing infrastructure, that is flexible over time, both to aid internal operations and create links to other regimes

• Encouraging adaption and change, to address errors and cope with new developments

Criticisms

A common pool resource is defined above by a set of characteristics, but a common property regime is an institution. The implicit idea is that certain resources may have a propensity to be governed by common property institutions. This concept has limited usefulness because it suppresses the co-evolution of resource scarcity and institutional governance. The most that economists have been able to show, according to Copeland and Taylor 2009, is that resource characteristics may be identified that lead an institution being eventually governed by one institution or another. Three forces determine success or failure in resource management: the regulator's enforcement power, the extent of harvesting capacity, and the ability of the resource to generate competitive returns without being extinguished. The transition of resource governance from open access to common property to regulated private property is less well understood.

Open access resources

Open access resources are, for the most part, rivalrous, non-excludable goods which makes them very similar to common goods during times of prosperity. Unlike many common goods, open access goods require little oversight or may be almost impossible to restrict access. However as these resources are first come, first serve they may be affected by the phenomenon of the tragedy of the commons. Two possibilities may follow a common property regime or an open access regime.

An open access regime is set up to continue the ideals of open access resource in which everything is up for grabs, i.e. land. This occurs in the expansion of the U.S. west where thousands of acres were given away to the first one to claim the land.

However in a different setting such as fishing there will drastically different consequences. Since fish are an open access resource it is relatively simple to fish and profit. If fishing becomes profitable there will be more fishers and less fish. Less fish leads to higher prices which will lead again to more fishers, as well as lower reproduction of fish. This is a negative externality and an example of problems with open access goods.

In today’s world there are a few changes to the meaning of open access resource. This of course has to do with the widespread use of information on the internet. These may be articles or works/research that anyone can access and use.[8] For more info visit open access.