A Brief Introduction to Environmental Economics

What is environmental economics?

Economics is a body of knowledge (a science) that has certain theories, values, methods, and assumptions. One goal of economists is to understand how to produce goods for society in the most efficient manner. This is achieved by having a better understanding of human activities in a market system.

Environmental economics is a distinct branch of economics that acknowledges the value of both the environment and economic activity and makes choices based on those values. The goal is to balance the economic activity and the environmental impacts by taking into account all the costs and benefits. The theories are designed to take into account pollution and natural resource depletion, which the current model of market systems fails to do. This “failure” needs to be addressed by correcting prices so they take into account “external” costs. External costs are uncompensated side effects of human actions. For example, if a stream is polluted by runoff from agricultural land, the people downstream suffer a negative external cost or externality.

The assumption in environmental economics is that the environment provides resources (renewable and non-renewable), assimilates waste, and provides aesthetic pleasure to humans. These are economic functions because they have positive economic value and could be bought and sold in the market place. However, traditionally, their value was not recognized because there is no market for these services (to establish a price), which is why economists talk about “market failure”. Market failure is defined as the inability of markets to reflect the full social costs or benefits of a good, service, or state of the world. Therefore, when markets fail, the result will be inefficient or unfavorable allocation of resources. Since economic theory wants to achieve efficiency, environmental economics is used as a tool to find a balance in the world’s system of resource use.

Another basic term in environmental economics is the idea of “scarcity.” Historically, goods and services provided by the environment were seen to be limitless, having no cost, thus not considered scarce. Scarcity is a misallocation of these services (which are not limitless) due to a pricing problem. If resources were properly priced to include all costs, then the resource could not be over-exploited because the actual cost would be too high. This is a powerful tool in environmental problems…proper pricing.

Environmental economics is not the same as ecological economics. Ecological economics is a new model with the basic premise being that market-based activities are not sustainable, so a “grand new theory” is needed to describe the world and determine how to conduct activities in a sustainable manner. It uses an entirely different framework. This paper will discuss only environmental economics.

The key to the environmental economics approach is that there is value from the environment and value from the economic activity…the goal is to balance the economic activity with environmental degradation by taking all costs and benefits into account.

What is environmental valuation?

In order to help correct economic decisions that often treat environmental functions as free, it is important to define and measure their value. Valuation measures human preferences for or against changes in the state of environments. It does not value the environment on its own. If there is no human attachment to it, then the service has no economic value. Although other types of value are often important, economic values are useful to consider when making economic choices – choices that involve tradeoffs in allocating resources.

“Measures of economic value are based on what people want – their preferences.

Economists generally assume that individuals, not the government, are the best judges

of what they want. Thus, the theory of economic valuation is based on individual

preferences and choices. People express their preferences through the choices and

tradeoffs that they make, given certain constraints, such as those on income or available

time. In a market economy, dollars (or some other currency) are a universally accepted

measure of economic value, because the number of dollars that a person is willing to pay

for something tells how much of all other goods and services they are willing to give up to

get that item. This is often referred to as ‘willingness to pay.’”

Many economists have been criticized for putting a ‘price tag’ on nature. However, decisions are being made every minute regarding resource allocation. These decisions are economic decisions and therefore are based on society’s values. In essence, the environment itself is not being valued, instead individual preferences for the environment are what are being measured and compared. Environmental valuation can be a useful, yet also difficult and controversial tool.

There are two types of values: use and non-use. ‘Use value’ is defined as the value derived from the actual use of a good or service, such as hunting, fishing, bird-watching, or hiking. Use values may also include ‘indirect uses,’ such as the value of a bug that a fish may eat, which then a fisherperson may catch. Though that bug is not directly used by the fisherperson, it has an indirect value because of its place in the food chain. A large part of environmental economics has been devoted to valuing ‘use’ services.

‘Non-use values,’ also referred to as ‘passive use’ values, are values that are not associated with actual use, or even the option to use a good or service. Existence value is a type of non-use value and is the value that people place on simply knowing that something exists, even if they will never see it or use it. Many people value the Amazon rainforest, even though they may never go there. Non-use value is the most difficult type of value to estimate.

Total economic value is the sum of all the relevant use and non-use values for a good or service.

How is valuation used? – Cost/Benefit Analysis

The main method used for valuation is cost-benefit analysis (CBA). This analysis is basically compiling the costs of a project as well as the benefits, then translating them into monetary terms and discounting them over time. (Discounting is the process of determining the present value of future benefits and costs.) Ideally, only projects with benefits greater than costs would be acceptable.

Cost - benefit comparisons have some problems. First, environmental benefits often lack market value, yet their costs are known. Second, benefits are often collected over time, while costs are up front. This creates a dilemma, since the question to be answered is in present time. Third, it is often difficult to understand what is being measured or to determine values for what is being measured. And fourth, results are often controversial and in some cases, could be used against you. However, it is good to remember that you are empowered just by describing each benefit, even if you can’t value it.

The first step is always to compare what would happen with and without the proposed project. Economic analysis is not possible without a clear understanding of how the project would affect the area. When this exercise is complete, the analyst should have a list of project impacts, classified according to the type of value they are likely to affect (use or non-use) and the group or groups that would benefit from the project.

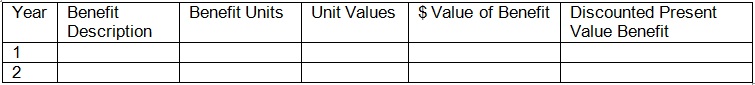

To continue with the analysis, one must next describe clearly what each benefit is and convert it into human needs. These need to be broken into measurable units, values per unit need to be established, and then discounted to the present value. For example:

There are several different methodologies used to determine the value of a benefit. Which methodology is used is often determined by the time and expense of the analysis.

The following methods are used :

1.)Market Price Method

Estimates economic values for ecosystem products or services that are bought and sold in commercial markets. For example, a cultural site could be valued based on the entrance fees collected.

2.) Productivity Method

Estimates economic values for ecosystem products or services that contribute to the production of commercially marketed goods. For example, the benefits of different levels of water quality improvement would be compared to the costs of reductions in polluting runoff.

3.) Hedonic Pricing Method

Estimates economic values for ecosystem or environmental services that directly affect market prices of some other good. Most commonly applied to variations in housing prices that reflect the value of local environmental attributes.

4.) Travel Cost Method

Estimates economic values associated with ecosystems or sites that are used for recreation. Assumes that the value of a site is reflected in how much people are willing to pay to travel to visit the site. For example, adding up the costs people would expend to travel and recreate at a particular area.

5.) Damage Cost Avoided, Replacement Cost, and Substitute Cost Methods

Estimate economic values based on costs of avoided damages resulting from lost ecosystem services, costs of replacing ecosystem services, or costs of providing substitute services. For example, the costs avoided by providing flood protection.

6.) Contingent Valuation Method

Estimates economic values for virtually any ecosystem or environmental service. The most widely used method for estimating non-use, or “passive use” values. It asks people to directly state their willingness to pay for specific environmental services, based on a hypothetical scenario. For example, people would state how much they would pay to protect a particular area.

7.) Contingent Choice Method

Estimates economic values for virtually any ecosystem or environmental service. Based on asking people to make tradeoffs among sets of ecosystem or environmental services or characteristics. It does not directly ask for willingness to pay—this is inferred from tradeoffs that include cost as an attribute. For example, a person would state their preference between various locations for siting a landfill.

8.) Benefit Transfer Method

Estimates economic values by transferring existing benefit estimates from studies already completed for another location or issue. For example, an estimate of the benefit obtained by tourists viewing wildlife in one park might be used to estimate the benefit obtained from viewing wildlife in a different park.

The researcher should first narrow the types of benefits by their importance and then balance accuracy and costs in choosing methods. Sometimes the easiest analysis often provides substantial benefits that show large values. Usually, a benefit measured from market-based techniques or various kinds of extractive use values are the easiest to measure. If one method alone provides an answer, then the analysis can stop. The data requirements and limitations of the methods should be taken into account when deciding which to use. Discounting, which is the process of reducing future benefits and costs to their present value, is the last step. Choosing an acceptable discount rate is often a challenging task. It is highly controversial since the rate chosen will have a big effect on the results of the analysis. Sometimes the discount rate is chosen by federal regulation.

Once more it should be noted that :

“Because it focuses only on economic benefits and costs, benefit-cost analysis

determines the economically efficient option. This may or may not be the same as

the most socially acceptable option, or the most environmentally beneficial option.

Remember, economic values are based on peoples’ preferences, which may not

coincide with what is best, ecologically, for a particular ecosystem. However, public

decisions must consider public preferences, and benefit-cost analysis based on ecosystem valuation is one way to do so.”

Why is environmental valuation important?

Currently, in the U.S., environmental valuation is used in five different ways:

- Project evaluation

- Regulatory review

- Natural resource damage assessment

- Environmental costing

- Environmental accounting

Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) is used in project evaluation and regulatory review. In the United States, CBA started out as an attempt to incorporate economic information in public investment decisions involving water resources. The Army Corps of Engineers was the first federal agency to develop economic analytical processes in their project evaluations.

In the early 1980’s, CBA became part of the requirements of regulatory review. President Ronald Reagan signed Executive Order #12291 in 1981, which was rescinded and changed by President Bill Clinton in 1993 to become Executive Order #12866. This order states that “significant regulatory actions require economic analysis.” This has changed the fundamental basis on which Agency rulemakings are evaluated. It requires that an Agency “shall…propose or adopt a regulation only upon reasoned determination that the benefits of the intended regulation justify its costs”. Some states are also adopting similar requirements for regulatory review. Washington State, for example, has a state law similar to the national executive order for legislative rules (Washington State RCW 34.05.328(1)(c)).

Natural resource damage assessment (NRDA) is another way that valuation is used in the U.S. The Comprehensive, Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), which was passed by Congress in December 1980, created “Superfund” to finance clean-up of waste sites and established a liability system for parties to pay for injuries to natural resources. The oil spill in 1989 by the Exxon Valdez in Alaska, brought natural resource litigation into the forefront and also produced the Oil Pollution Act, which dealt primarily with natural resource damages. The National Marine Sanctuary Act and the Park System Resource Act also have liability provisions for injuries to protected resources from any source.

Environmental costing is used in decisions regarding investments and operation. The costs of producing something along with the social costs (including external costs) are all included in the cost of the good. It has been used in the energy sector and somewhat in waste disposal.

Environmental accounting is a way to account for the services of environmental assets within the framework of economic activity or business. It is an assessment and evaluation of the results, costs, and savings attributable to environmental protection activities. Some examples include pollution prevention, environmental life cycle assessment or environmental performance reporting.

It is clear that environmental economics is being used more often for discussing environmental issues. Whether utilized as a tool to determine which projects have the greatest benefits or to determine natural resource damages, those individuals who have an understanding of some of the concepts, will have a distinct advantage.

How to use the resources on ELAW’s website

There are a wide variety of resources in the “Economics” resource section of ELAW’s website that can help environmental lawyers, depending on their goals.

Economics: General Information

For a more in-depth understanding of the basic concepts discussed in this paper, the web page “Ecosystem Valuation” (www.ecosystemvaluation.org) does a very good job of laying out these ideas. Many of the publications on ELAW’s website have been downloaded from the World Bank Group Environmental Economics and Indicators site (lnweb18.worldbank.org/ESSD/envext.nsf/44ByDocName/EnvironmentalEconomicsandIndicators). Under the sub-heading “Other Resources” (www.elaw.org/resources/text.asp?id=1999), is a compilation of environmental economic journals, which also provide relevant material (sometimes at a cost). Under the sub-heading “Related Links” then “Guide to Environmental Economics Textbooks” (www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpa15/envecontexts.pdf), a world-renowned environmental economist has compiled a listing of textbooks and his recommendations that may be useful to persons who want a more in-depth understanding of this area.

Many of the “Related Links” are of an international nature and provide a variety of information (www.elaw.org/resources/topical.asp?topic=Economics).

Economics: Natural Resource Damages

From a legal standpoint, the paper titled “What is the Role of Environmental Valuation in the Courtroom?” (www.elaw.org/resources/text.asp?id=2039) gives an overview of how valuation is used, mostly from a natural resource damage angle. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has a damage assessment and restoration program, which has lots of useful information if one is determining damages (www.darp.noaa.gov/legislat.htm).

Economics: Regulatory and Incentive Systems

From a regulatory viewpoint, the paper from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) titled “OAQPS Economic Analysis Resource Document” (www.elaw.org/resources/text.asp?id=1997) outlines the guidelines used for regulatory analysis. In addition the U.S. EPA National Center for Environmental Economics website, (yosemite.epa.gov/ee/epa/eed.nsf/webpages/homepage) has more information. Also the link “Guidelines and Discount Rates for Benefit-Cost Analysis of Federal Programs” (www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/a094/a094.html#top) is very comprehensive.

There are also several relevant laws on the ELAW site.

Economics : Valuation Methods

The paper titled “Economic Analysis of Investments in Cultural Heritage” (www.elaw.org/resources/text.asp?id=1976) gives a simple comparison between various valuation methodologies. Also, the paper titled “Economic Valuation of Health Impacts” (www.elaw.org/resources/text.asp?id=1978) is a good example of how environmental economics can be used to influence decision makers.

I hope that this information will be useful. To be able to quantify environmental services is often more persuasive than just making general statements. The growth of literature and organizations in this area show the potential of what can be accomplished.